Questions? Need help placing your order?

Email us at sales@wordonfire.org or call 866-928-1237.

CUSTOM JAVASCRIPT / HTML

The cultural moment in which we find ourselves today demands, possibly more than any other time in history, a New Apologetics...

The cultural moment in which we find ourselves today demands, possibly more than any other time in history, a New Apologetics...

For Christians, apologetics, or giving a reasoned explanation or defense of the faith, is a necessity and duty. Yet the cultural moment in which we find ourselves today demands, possibly more than any other time in history, a The New Apologetics—a potent and spirited renewal of apologetics that reaches new audiences, takes new approaches, looks to new models, and tackles new issues.

This groundbreaking collection is a bold first step toward making this renewal a reality. Featuring over forty essays from many of today’s leading Catholic apologists, theologians, and philosophers, The New Apologetics charts a new course for the future of apologetics: a smart, joyful, and beautiful defense of the faith, one that appeals to both the head and the heart. Though it contains many arguments within its pages, it offers something more fundamental: a prelude to systematic argumentation. Arguments are no good if they are not heard, and The New Apologetics is a kind of intellectual and tactical map for the apologist who wants to be heard in today’s world.

During his apostolic journey to the United States in 2008, Pope Benedict XVI insisted that “the Church needs to promote at every level of her teaching—in catechesis, preaching, and seminary and university instruction—an apologetics aimed at affirming the truth of Christian revelation, the harmony of faith and reason, and a sound understanding of freedom.” There is an urgent need for the whole Church to respond to this papal summons—and The New Apologetics is just the place to start.

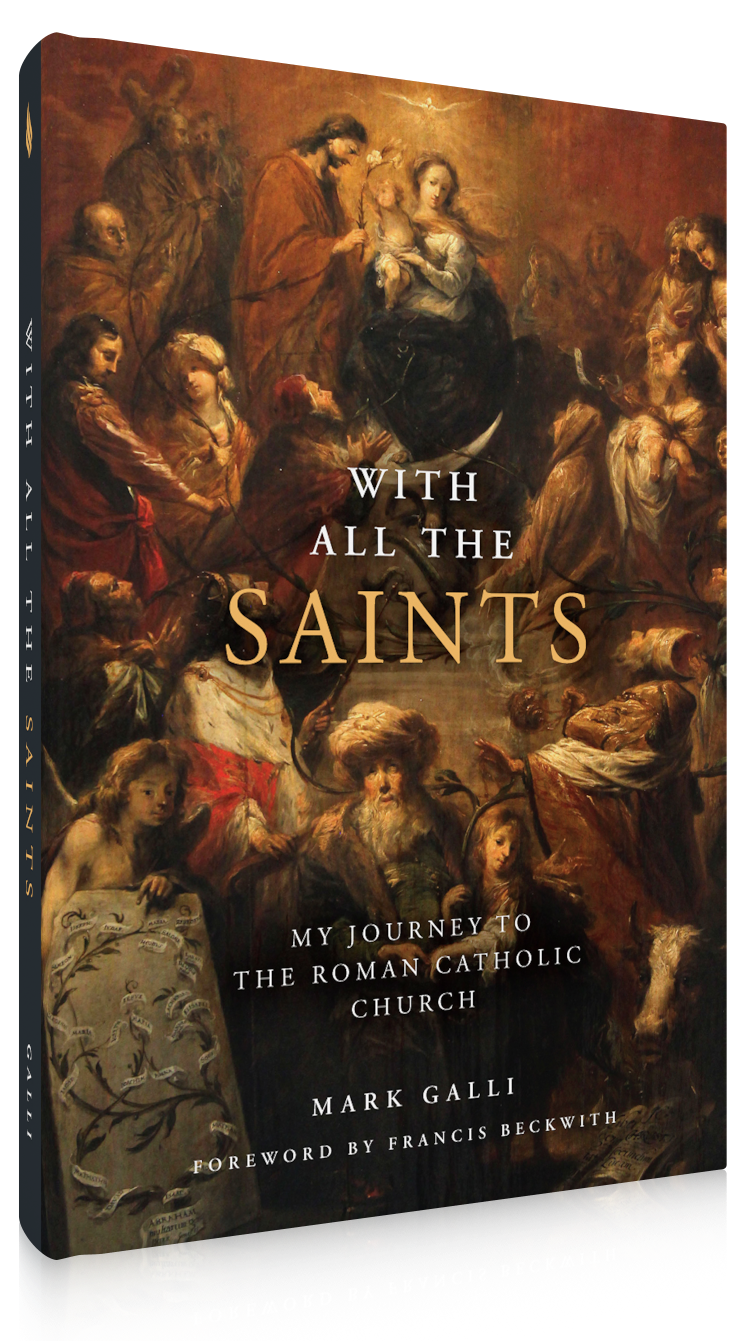

Mark Galli was the editor in chief of Christianity Today for seven years, a Presbyterian pastor for ten years, and a passionate evangelical Protestant since first responding to an altar call in 1965 at thirteen years old. But in 2020, Galli formally returned to the faith in which he was baptized as an infant: the Roman Catholic Church.

With All the Saints: My Journey to the Roman Catholic Church is the compelling memoir of one man’s search for the fullness of truth. Through honest and engaging storytelling, Galli recounts the various spiritual, theological, mystical, and ecclesial tributaries that led him to “cross the Tiber” back to Catholicism. Each tradition he passed through—Evangelical, Presbyterian, Episcopalian, Anglican, and Eastern Orthodox—he embraced without satisfaction and left without bitterness, drawing him finally to the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church: a Church of saints and sinners, all striving together in the great company of heaven; a Church that he could finally call home.

Honest, insightful, and entertaining, With All the Saints is a memorable love letter to Christ and his Church.

The New Apologetics: Defending the Faith in a Post-Christian Era

Edited by Matthew Nelson

Published by Word on Fire on June 13, 2022

Paperback | 288 Pages | 6" x 9"

2023 Association of Catholic Publishers Excellence in Publishing Award Finalist!

Retail Price: $24.95

Launch Special: $19.96

(Get 20% OFF & Free U.S. Shipping!)

1

shipping

Where To Ship Book?

2

Your Info

Confirm Order

Your Shipping Address (U.S.A. Only):

* 100% Secure. Offer Only Available to Residents of the U.S.A. Having trouble with Internet Explorer? Try using Google Chrome.

Book

Amount

$19.96 (20% OFF + Free U.S. Shipping!)

$19 (37% OFF!)

Your order has been declined. Please double check your Credit Card Details or contact support for information.

Card Number:

CVC:

Expiry Month:

Expiry Year:

Order Summary

Order Total (Free U.S. Shipping!)

Dynamically Updated

$XX.00

LIMITED-TIME OFFER - $19 (37% OFF): Building on the call of the Second Vatican Council for a greater appreciation of Scripture, The Wisdom of the Word invites Catholics who are thinking about leaving the Church, or who are confused about elements of Catholic faith and practice, to pause and give the Bible a chance to illuminate their way. From the infighting among the Catholic faithful to the sins of Catholic leaders, and from Christ’s sacrifice on the cross to the Church’s emphasis on caring for the poor, theologians Michael Dauphinais and Matthew Levering explore common challenges to the faith in light of the timeless insights of the Word.

* 100% Secure & Safe Payments *

Questions? Need help placing your order?

Email us at sales@wordonfire.org or call 866-928-1237.

USPS Media Mail: Average Shipping Time = 7-10 Business Days

ABOUT the EDITOR

Matthew Nelson is an apologetics consultant and Teaching Fellow of the Word on Fire Institute. He holds a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) degree from the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College and is pursuing a master’s degree in philosophy from Holy Apostles College and Seminary. He has contributed articles to a variety of publications, including Evangelization & Culture, Church Life Journal, and Catholic Answers Magazine. He is the author of Just Whatever: How to Help the Spiritually Indifferent Find Beliefs That Really Matter. He is a Scholar Associate of the Society of Catholic Scientists.

WHAT PEOPLE are SAYING

“While reading Mark Galli’s wonderful account of his own journey to Catholicism, I found myself thinking about the evangelical world from which we both departed and what it was that ultimately carried us across the Tiber and into the Church. . . . Galli’s story, like each story of conversion or return, is unlike any other, and yet it is directed by the same Spirit that has for generations moved all those uneasy hearts that eventually find their rest in the barque of Peter.”

- Francis Beckwith, from the foreword

“‘Conversion—it's complicated,’ writes Mark Galli at the start of this winsome spiritual memoir, and isn't that the truth? He explains his own with relatable stories and unique clarity, honoring each of the religious places he has been along the way. This book is an example of loving your neighbor.”

- Jon M. Sweeney, author of Feed the Wolf: Befriending Our Fears in the Way of Saint Francis

“At a time when things feel increasingly polarized and even faith institutions seem filled with factions demanding ‘either/or,’ Mark Galli beautifully articulates the much-needed, balanced, and reasonable ‘both/and’ that resides so reliably within Catholic theology, thought, and practice. With affectionate and respectful salutes to the Protestant traditions that have formed him in faith over a lifetime, Galli's learned analysis perfectly complements his honest and human voyage through the Christian ‘tributaries’ of Evangelicalism and Anglicanism (with a brief drift into Orthodoxy), before finally encountering the Tiber and mooring himself to the barque of Peter. Filled with insights and helpful analogies, With All the Saints is a valuable, unique, and highly readable testimonial that Catholics and non-Catholics alike will find identifiable, illuminating, and entertaining.”

- Elizabeth Scalia, Editor-at-Large, Word on Fire Institute, and author of Strange Gods and Little Sins Mean a Lot

“Like St. John Henry Newman’s Apologia, Mark Galli’s account of his return to the Catholic faith of his Baptism is above all the story of a well-formed conscience, seeking the truth in good faith. I can think of no book I would be more likely to send to a Protestant friend.”

- Matthew Walther, Editor, The Lamp magazine

TABLE of CONTENTS

Foreword - Cardinal Thomas Collins

Acknowledgments - Matthew Nelson

Introduction - Matthew Nelson

PART I – NEW AUDIENCES

1 - Nones Are Not “Nothings” – Stephen Bullivant

2 - Awakening the Indifferent – Bobby Angel

3 - Why Catholics Fall Away: A Priest’s Perspective – Fr. Blake Britton

4 - The Reason and the Remedy: Bringing the Lapsed Christian Home

– Tod Worner

5 - Moral Relativism: Arguments For and Against – Francis J. Beckwith

6 - Countering Scientific Materialism – Stephen Barr

– Tod Worner

PART II – NEW APPROACHES

7 - Digital Apologetics: Defending the Faith Online – Brandon Vogt

8 - New Epiphanies of Beauty – Michael Stevens

9 - Sowing “Seeds of the Word” – Andrew Petiprin

10 - The Heart of Affirmative Orthodoxy – John L. Allen Jr.

11 - Truth, Meaning, and the Christian Imagination – Holly Ordway

PART III – NEW MODELS

12 - Socrates – Trent Horn

13 - St. Augustine – Matthew Levering

14 - St.Thomas Aquinas – John DeRosa

15 - Blaise Pascal – Peter Kreeft

16 - G.K. Chesterton – Dale Ahlquist

17 - C.S. Lewis – Fr. Michael Ward

18 - Flannery O’Connor – Matthew Becklo

19 - René Girard – Grant Kaplan

20 - Joseph Ratzinger – Richard DeClue

PART IV – NEW ISSUES

Science and Faith

21 - Theology and Science: How and Why – Christopher Baglow

22 - Defending a Historical Adam and Eve in an Evolving Creation

– Fr. Nicanor Pier Giorgio Austriaco, OP

23 - Free Will and Its Challenges from Neuroscience – Daniel De Haan

24 - The Quantum Revolution and the Reconciliation of Science and Humanism – Robert C. Koons

25 - Creation and the Cosmos – Jonathan Lunine

26 - Artificial Intelligence: Religion of Technology – Fr. Anselm Ramelow, OP

– Fr. Nicanor Pier Giorgio Austriaco, OP

Psychology and Anthropology

27 - Psychology and Religion – Christopher Kaczor

28 - Happiness and the Meaning of Life – Jennifer Frey

29 - Matters of Life and Death – Stephanie Gray Connors

30 - Anthropological Fallacies – Ryan T. Anderson

31 - The “Fourth Age” of Human Communications – Jimmy Akin

Theology and Philosophy

32 - The Threefold Way – Fr. James Dominic Brent, OP

33 - New Challenges to Natural Theology – Edward Feser

34 - Doubt and Certainty – Tyler Dalton McNabb

35 - The Existence of the Immortal Soul – Turner C. Nevitt

36 - Dark Passages of the Bible – Matthew J. Ramage

37 - Resurrection and the Future – David Baird

38 - Ecumenical Apologetics – Archbishop Donald Bolen

Atheism and Culture

39 - The Mirror of Evil – Eleonore Stump

40 - The Argument from Divine Hiddenness – Fr. Gregory Pine, OP

41 - Wokeness and Social Justice – Matthew R. Petrusek

Afterword - Bishop Robert Barron

Recommended Resources

Contributors

TABLE of CONTENTS

Foreword - Cardinal Thomas Collins

Acknowledgments - Matthew Nelson

Introduction - Matthew Nelson

PART I – NEW AUDIENCES

1 - Nones Are Not “Nothings” – Stephen Bullivant

2 - Awakening the Indifferent – Bobby Angel

3 - Why Catholics Fall Away: A Priest’s Perspective – Fr. Blake Britton

4 - The Reason and the Remedy: Bringing the Lapsed Christian Home

– Tod Worner

5 - Moral Relativism: Arguments For and Against – Francis J. Beckwith

6 - Countering Scientific Materialism – Stephen Barr

– Tod Worner

PART II – NEW APPROACHES

7 - Digital Apologetics: Defending the Faith Online – Brandon Vogt

8 - New Epiphanies of Beauty – Michael Stevens

9 - Sowing “Seeds of the Word” – Andrew Petiprin

10 - The Heart of Affirmative Orthodoxy – John L. Allen Jr.

11 - Truth, Meaning, and the Christian Imagination – Holly Ordway

PART III – NEW MODELS

12 - Socrates – Trent Horn

13 - St. Augustine – Matthew Levering

14 - St.Thomas Aquinas – John DeRosa

15 - Blaise Pascal – Peter Kreeft

16 - G.K. Chesterton – Dale Ahlquist

17 - C.S. Lewis – Fr. Michael Ward

18 - Flannery O’Connor – Matthew Becklo

19 - René Girard – Grant Kaplan

20 - Joseph Ratzinger – Richard DeClue

PART IV – NEW ISSUES

Science and Faith

21 - Theology and Science: How and Why – Christopher Baglow

22 - Defending a Historical Adam and Eve in an Evolving Creation

- Fr. Nicanor Pier Giorgio Austriaco, OP

23 - Free Will and Its Challenges from Neuroscience – Daniel De Haan

24 - The Quantum Revolution and the Reconciliation of Science and Humanism - Robert C. Koons

25 - Creation and the Cosmos – Jonathan Lunine

26 - Artificial Intelligence: Religion of Technology – Fr. Anselm Ramelow, OP

- Fr. Nicanor Pier Giorgio Austriaco, OP

Psychology and Anthropology

27 - Psychology and Religion – Christopher Kaczor

28 - Happiness and the Meaning of Life – Jennifer Frey

29 - Matters of Life and Death – Stephanie Gray Connors

30 - Anthropological Fallacies – Ryan T. Anderson

31 - The “Fourth Age” of Human Communications – Jimmy Akin

Theology and Philosophy

32 - The Threefold Way – Fr. James Dominic Brent, OP

33 - New Challenges to Natural Theology – Edward Feser

34 - Doubt and Certainty – Tyler Dalton McNabb

35 - The Existence of the Immortal Soul – Turner C. Nevitt

36 - Dark Passages of the Bible – Matthew J. Ramage

37 - Resurrection and the Future – David Baird

38 - Ecumenical Apologetics – Archbishop Donald Bolen

Atheism and Culture

39 - The Mirror of Evil – Eleonore Stump

40 - The Argument from Divine Hiddenness – Fr. Gregory Pine, OP

41 - Wokeness and Social Justice – Matthew R. Petrusek

Afterword - Bishop Robert Barron

Recommended Resources

Contributors

READ the AFTERWORD by BISHOP BARRON

READ the AFTERWORD by

BISHOP BARRON

In a 1983 address to the bishops of Latin America, Pope John Paul II, very much in line with the missionary élan of the Second Vatican Council, called for a New Evangelization—a proclamation of the Gospel that is new in ardor, new in methods, and new in expression.

While this call remains as urgent as ever, I can verify, on the basis of over twenty years of ministry in the field of evangelization, that a vitally needed aspect of the New Evangelization is a New Apologetics—a revivified defense of the Catholic faith. Innumerable studies over the past ten years have confirmed that people frequently cite intellectual reasons when asked what prompted them to leave the Church or lose confidence in it. These concerns remain crucial stumbling blocks to the acceptance of the faith, especially among the young.

I realize that in some circles within the Church, the term “apologetics” is suspect, since it seems to indicate something rationalistic, aggressive, condescending. I hope it is clear that arrogant proselytizing has no place in our pastoral outreach, but I hope it is equally clear that an intelligent, respectful, and culturally sensitive explication of the faith—giving a reason for the hope that is within us, as St. Peter exhorts (1 Pet. 3:15)—is certainly necessary. The term “apologetics” is derived from the Greek apologia, which simply means “bringing a word to bear.” It implies, therefore, giving a reason, providing a context, putting things in perspective, offering direction. And people today are hungry and thirsty—not just for friendly companions, but for a word from the Church.

What would this New Apologetics look like? First, it would engage new audiences. By far the fastest-growing “religious” group in the United States is the “nones”—that is, those who claim no religious affiliation. In 1970, only 3% of the country self-identified as nones. Today, that number has risen to 25%. When we focus on young people, the picture is even more bleak. Almost 40% of those under thirty are nones, and among young people who were raised Catholic, the number rises to 50%. This rapidly growing audience of nonreligious men and women—atheists, agnostics, and former Catholics, especially—should be the target of the New Apologetics.

Secondly, it would take new approaches to presenting the faith, which engage not only the mind but the whole person. It would utilize the new media, find “seeds of the Word” in the culture, engage the imagination, joyfully champion what orthodox Catholicism stands for, and perhaps most crucially, lead with beauty. Especially in our postmodern cultural context, commencing with the true and the good is often a nonstarter. However, the beautiful often proves a more winsome, less threatening path. And part of the genius of Catholicism is that we have so consistently embraced the beautiful—in song, poetry, architecture, painting, sculpture, and liturgy. All of this provides a powerful matrix for evangelization.

Thirdly, it would take inspiration from new models. Catholicism is a smart religion, and another one of its great virtues is that it has a rich and deep theological tradition. Taking Mary as its model, Catholicism “ponders” revelation and seeks to understand it, using all of the intellectual tools available. A New Apologetics would follow great ponderers of the Word such as Augustine, Aquinas, Pascal, Chesterton, Lewis, and many others in order to meet pressing objections to the faith.

Finally, a New Apologetics would confront new issues, especially the kinds of questions that young people are spontaneously asking today. These would include queries about God’s existence, the Bible, the meaning of life, and especially the relationship between religion and science. For many people today, “scientific” and “rational” are equivalent. And therefore, since religion is obviously not scientific, it must be irrational. Without for a moment denigrating the sciences, new apologists have to show that there are nonscientific and yet eminently reasonable paths that conduce toward knowledge of the real. Literature, drama, philosophy, the fine arts—all close cousins of religion—not only entertain and delight; they also bear truths that are unavailable in any other way. A renewed apologetics ought to cultivate these approaches.

We find a template for this New Apologetics in the story of Christ’s conversation with two erstwhile disciples on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:13– 35). Jesus walks with them in easy fellowship, even though they are going the wrong way, and he gently asks what’s on their minds. But this invitational approach aroused questions that called for answers. Jesus then taught—with clarity, at length, and in depth. How wonderful that, recalling Jesus’ great apologetic intervention, the Emmaus disciples said, “Were not our hearts burning within us while he was talking to us on the road, while he was opening the scriptures to us?”

This collection of essays from many of today’s leading Catholic thinkers and evangelists offers, with considerable clarity and panache, a bold first step in the direction of this renewed vision for apologetics. My hope is that it helps to inaugurate a new era of intellectual vigor for the Church, one in which an army of apologists both walk and talk with those on the road, offering—with “gentleness and reverence” (1 Pet. 3:16), but also boldness and intelligence—a reason for their hope. This, I trust, will set wandering hearts on fire.

SAMPLE the ADVENT REFLECTIONS for FREE

Read Dr. Kreeft's introduction and his reflections for all four Sundays of Advent. Click the button below to download a free PDF sample...

ABOUT the BOOK

Vatican II called the Bible “the support and energy of the Church,” “the pure and everlasting source of spiritual life,” and “the food of the soul.” Yet, for many Catholics, their engagement with Scripture is often limited to what they hear at Mass—and the dull, safe, predictable homilies that obscure rather than break open up the Word of God.

In Food for the Soul, the first book in a riveting three-part series, celebrated philosopher Peter Kreeft invites the faithful—clergy and laity alike—to a heart-to-heart relationship with Christ the Word through the Word of the Scriptures. Moving through the First Reading, Second Reading, and Gospel Readings for each Sunday and other major liturgical celebrations throughout the three-year lectionary cycle, Kreeft brings the Mass readings to life with his trademark blend of gentle wit and unyielding wisdom, challenging readers to plant their souls in the rich soil of Scripture and sharpen their minds with the Sword of the Spirit.

Whether you are a layperson looking for additional insight on the readings at Mass, or a priest or deacon looking for inspiration for a homily, Food for the Soul is a gift to the whole Church from one of today’s greatest Christian writers.

TABLE of CONTENTS

Introduction

Advent

Christmas Time

Lent

Holy Week

Easter Time

Ordinary Time

CUSTOM JAVASCRIPT / HTML